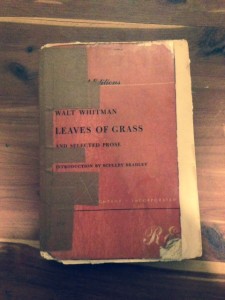

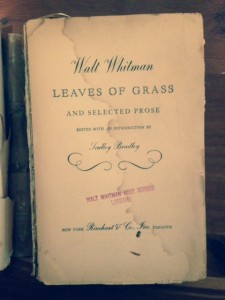

Walt Whitman High School is set in a woodsy South Huntington neighborhood, about one mile from Whitman’s birthplace. I still have a copy of Leaves of Grass that I neglected to return to the Whitman library before I graduated in 1980. I’m not proud of my theft but I treasure the book. None of my teachers assigned any of it but I spent a lot of time picking through it on my own in a “study hall” during the spring of my senior year. I’ve dipped into it often in subsequent years. It’s musty, falling apart and held together with packing tape, but it still boots up every time I open it. The book, not just the content of the book, but the book, serves as a mystic connection among different stages of my life, my professional choices, people who have mentored or inspired me – and Walt.

The poem to which I have most returned is “By Blue Ontario’s Shore.” It’s a nostalgic poem for a nation that had lost it’s muse. Whitman revised it after the Civil War and speaks of the need for poets and teachers to seek and study the essential stuff and source material of America in order to find the inspiration needed to heal and serve her. It contains a tough challenge which intimidated me as a young social studies teacher:

Are you he who would assume a place to teach or be a poet here in

the States?

The place is august, the terms obdurate.

Who would assume to teach here may well prepare himself body and mind,

He may well survey, ponder, arm, fortify, harden, make lithe himself,

He shall surely be question’d beforehand by me with many and stern

questions.

Who are you indeed who would talk or sing to America?

Who was I indeed! My first social studies department was packed with bright and seasoned New York City teachers. They argued a lot in delicious debates that had been going on since the nineteen-sixties. Probably longer. My first chairman (they used that term then) was a veteran of the Great Depression and of horrific amphibious landings in the South Pacific. He was a graduate of Columbia University and the author of an Economics textbook. He knew stuff; seemingly everything. The above Whitman passage would, years later, be quoted in his eulogy. When they hired me I was twenty-three and, like many new teachers, figuring it out as I went along. Surely, Whitman demanded more than I had in me at the time:

Have you studied out the land, its idioms and men?

Have you learn’d the physiology, phrenology, politics, geography,

pride, freedom, friendship of the land? its substratums and objects?

Have you consider’d the organic compact of the first day of the

first year of Independence, sign’d by the Commissioners, ratified

by the States, and read by Washington at the head of the army?

Have you possess’d yourself of the Federal Constitution?

Do you see who have left all feudal processes and poems behind them,

and assumed the poems and processes of Democracy?

Though I had degrees in History and Politics it would take years of teaching, of working with more experienced colleagues, of graduate school and of just living an adult life before I could claim to understand the ongoing conversations about how we should rule ourselves or about what held America together. It would be years before I developed real skill in bringing teenagers into those conversations. Though I was not aware of it at first, Whitman also offered sensible advice for those on the path to becoming good teachers:

Are you faithful to things? do you teach what the land and sea, the

bodies of men, womanhood, amativeness, heroic angers, teach?

Have you sped through fleeting customs, popularities?

Can you hold your hand against all seductions, follies, whirls,

fierce contentions? are you very strong? are you really of the

whole People?

Are you not of some coterie? some school or mere religion?

The past thirty years have presented many educational customs and whirls as well as imposing and fierce contentions, and coteries that seem to demand one’s “buy in.” Most of these are well-intended, based on at least partial truths and are even useful. Some demand scrutiny and wariness. I’m fortunate to have come of age at a time and in places that reinforced what I see as two essential objectives for young teachers:

- Know well your students and the content of the subjects you teach and

- Take a skeptical (not cynical!) stance against ideologies, schools-of-thought, technologies and pedagogies.

I read the slim volumes sent to me from the ASCD bookstore. I have a shelf of books about multiple intelligences, teaching with tablets, nurturing “grit,” and teaching 21st century skills. Some of these books definitly help me operationalize the current regulations and “standards” that frame my professional responsibilities. I can’t think of any that would be worth stealing, let alone keeping for thirty-five years.

Most of our educational traditions have something to offer, even if they include extremes against which we must be on guard. The latest batch of enthusiasms can all be placed within the context of an old conversation about what and how to teach. Though we need not reject them out of hand, we must at least question the thinking of our current gurus and of the most influential among those who would presume to shape the way we teach here in the States. Indeed, it is our duty to ask how well they advance the chief end of education – at least public education – which is to prepare our youth to take on the responsibilities of citizenship. Everything else is secondary.